Short Explanation

The PowerShell pipeline is a core concept that allows the output of one command or operation from the left side of the | (Pipe) to be fed as an input to a command or operation on the right. $_ Variable

Command-One | Command-Two | Command-Three

Command-One performs something, then gives its results through the pipeline to Command-Two. The second command then does something to the results, and passes its output to Command-Three. After Command-Three’s operation, the results are finally given.

Long Explanation

Okay, it’s a lot more complicated than that. If you just start plugging together PowerShell commands like you’re Frankenstein you may be quickly disappointed and presented with various errors. So let’s try and give some more nuance to this.

Let’s take a single command, and slowly build up to the pipeline. Run the below:

Get-Service

That was a nice scroll wasn’t it? So here we are, presented with a long list, a common occurrence in your scripting journey. We probably don’t want all these results. Maybe we’re looking for a service, but we don’t know its name, (yes you may just have a shot in the dark with guessing the name). We just know that something is running and we need to find it.

Well, first things first, this long list, what is it. What actually are the results. Is it just a text list? If we are going to be feeding the output of this command to another, we need to understand what we’re actually outputting.

Let’s start by setting a variable with the output of the command as the contents. This way, we can perform a common .gettype() method which is a simple way of finding out what type of data we’re working with.

$services = Get-Service

$services.gettype()

So we have a System.Array, which is for all intents and purposes, a list. That makes sense, we have a list of services. So, whatever command we’re using after the pipeline, will be receiving an array as input.

You can skip this little bit but while we’re here we can also see what is in the array. Let’s choose the first item of the

$servicesvariable and check its type:

$services = Get-Service

$services[0].GetType()

This tells us that

Get-Servicegives us an array (list) ofServiceControllerobjects. i.e. each service in that list is aServiceController. You don’t need to fully understand what that means just yet but this is helpful for later.

Okay, so let’s just use Where-Object, which is a very versatile command that lets us filter the output. We would like to find the services where “Status” is “Running”:

Get-Service | Where-Object -Property Status -eq "Running"

Much shorter list now, so what did the we do here.

We ran Get-Service and instead of printing out the full list of services, ==we== passed the list to the Where-Object cmdlet which filtered the list down to only the services that had the “Running” status. The output of this second command was then given to us.

So let’s just add another command, let’s sort the list in reverse alphabetical order by the display name of the service, and format a table to see only the status and display name.

Get-Service | Where-Object -Property Status -eq "Running" | Sort-Object -Property DisplayName -Descending | Format-Table -Property DisplayName, Status

So we fed the output of each command left of a pipe, across to the right as an input. Key point is to understand that we are not seeing the output of Get-Service, Where-Object, or Sort-Object. We are only seeing results of the right-most command in the pipeline: Format-Table.

The below breakdown shows how we are manipulating the data as we go through the pipeline:

Get-Service

| (Array of ServiceController objects)

V

Where-Object -Property Status -eq "Running"

| (Array of ServiceController objects)

| ( Status = "Running" )

V

Sort-Object -Property DisplayName -Descending

| (Array of ServiceController objects)

| ( Status = "Running" )

| ( Reverse sorted by DisplayName )

V

Format-Table -Property DisplayName, Status

| (Array of ServiceController objects)

| ( Status = "Running" )

| ( Reverse sorted by DisplayName )

| ( Formatted in a table )

V

DisplayName Status

----------- ------

Zoom Sharing Service Running

WWAN AutoConfig Running

Workstation Running

WLAN AutoConfig Running

WinHTTP Web Proxy Auto-Discovery Service Running

Windows Update Running

...

Example practical application

ipconfig

Okay, lets use the pipeline to look for a pattern (matching text):

ipconfig | Select-String -Pattern 'IPv4'

or:

ipconfig | Select-String -Pattern 'Default Gateway'

The really long explanation

Okay, so it does go somewhat deeper. Though if you have grasped the above fairly well, this shouldn’t be too bad.

Not all commands take Pipeline input

You cannot just put any old command after the |, it has to actually accept a pipeline input. You can find this out by using Get-Help with -parameter * (* because you’d like to read all parameters for the cmdlet).

Get-Help Set-Service -Parameter *

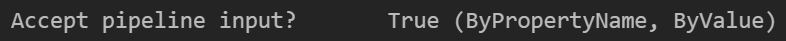

You’ll notice that for each parameter there is a Accept pipeline input? True/False line that will inform you if that parameter is compatible with a pipeline input. If the output of this had “false” for every single parameter, the command could not be used on the right side of a |.

You may have noticed that for the parameters that show “True”, next to them in brackets are ByPropertyName , ByValue, or both. This describes what type of input the parameter can take from the left side of the |. This is an absolute nightmare to explain, so I’ll try and simplify it as much as possible.

Types of Pipeline Input

Here is the print out for the Stop-Service command, and it’s -name parameter:

Get-Help Stop-Service -parameter Name

Understanding the syntax of Get-Help is important here. After the -Name parameter, a <System.String[]> is expected. This means, an array ([]) of Strings (it can also just take a single string, as PowerShell is kind and will infer that one string is kind of the same as an array of strings, but with only 1 item).

So let’s say we wanted to stop “Remote Desktop Services”:

Get-Service "Remote Desktop Services"

So we’re looking to supply “TermService” to the Stop-Service command.

The parameter -name says it can take pipeline input, and can do so using both methods: ByPropertyName , ByValue.

What we ==are== going to do, is show how both of these types of input are processed. Just to be completely clear on what we are doing, here’s an attempt at describing the functionality of the pipeline input methods:

Think of <input> as a command or variable that we’re running, and some-command as the command we use on the right side of the | that accepts pipeline input.

In both examples of ByValue and ByPropertyName, the two lines in each block are “equivalent” to each other. The | is helping us hand-over the value to the right side. This will really make a shit-ton of sense later on, so please just keep reading, the mental pay-off is bangin.

For ByValue:

<input> | Some-Command

Some-Command <input>

For ByPropertyName (If unclear, please refer to $_ Variable)

<input> | Some-Command -someProperty $_.someProperty

Some-Command -someProperty <input>.someProperty

ByValue

ByValue, literally just means feed it a value, and it will be inferred. So because -name expects a string. We could just write:

"TermService" | Stop-Service

We have a string, and feeding that string as an input to Stop-Service through the pipe. This is then inferred to be the value of the required -name parameter and the command can run.

ByPropertyName

This type of pipeline input means that whatever is left of the pipeline, has to have a property that matches the name of the parameter on the right. In this case, since we are providing a value to the -name parameter. We have to feed in an object with a name property.

First let’s create the object:

$inputObject = New-Object PSObject -Property @{

name = "TermService"

}

$inputObject

This creates an object of type “PSObject” (generic object) with a “name” property of value “TermService”.

This time round, we have an object, so we can access its property like:

$inputObject = New-Object PSObject -Property @{ name = "TermService" }

$inputObject.name

$inputObject.name.GetType()

This shows us that $inputObject.name contains “TermService”. The results under that, show that the value is a String. Which we know corresponds to the value expected by the -name parameter of Stop-Service.

Therefore:

$inputObject | Stop-Service

Would work using the ByPropertyName method of accessing pipeline input. As -name parameter will intrinsically match up with $inputObject.name.

Accepted Pipeline Input

In the example above, the Stop-Service cmdlet allows both ByValue, and ByPropertyName types of pipeline input. This is rare. In most cases, there is only one type allowed. Therefore it’s important that you know how to utilise both.

If you are sure you understand this, please skip to the next section. Otherwise here’s one final example:

Let’s imagine we have a command that updates our devices’ clock to the current local time.

Restore-LocalTime

Now for the purposes of this example, we’ll say that we wrote this command with a parameter for -DeviceName. So the command can be used like this:

Restore-LocalTime -DeviceName "My-PC-Name"

This will magically run for the my device, and reset my clock to local time. Or using an array let’s give it some more pc’s.

Restore-LocalTime -DeviceName @("My-PC-Name", "Your-PC-Name")

With this, I’ve now repaired both our clocks.

Great. So now let’s imagine how this command could take pipeline input. Let’s first, pose the scenario that the -DeviceName parameter only accepts ByValue method.

So let’s pretend that when we run Get-Help Restore-LocalTime -Parameter DeviceName:

-DeviceName <System.String[]>

Specifies the device names to restore local time for.

Required? true

Position? 0

Default value None

Accept pipeline input? True (ByValue)

Accept wildcard characters? false

So now we know, we just have to feed it a string, or an array of strings in order for the pipeline input to work.

$devices = @(

"My-PC-Name",

"Your-PC-Name",

"Your-Mums-PC-Name"

)

$devices | Restore-LocalTime

This would be the correct approach for feeding pipeline input. We are simply giving a variable that contains the array of device names (so basically we’ve just got the array on the left side of the |). Since -DeviceName is expecting a string array, or something that PowerShell could cleverly convert to a string array. We are golden.

So, what if instead, we ran Get-Help Restore-LocalTime -Parameter DeviceName and got:

-DeviceName <System.String[]>

Specifies the device names to restore local time for.

Required? true

Position? 0

Default value None

Accept pipeline input? True (ByPropertyName)

Accept wildcard characters? false

We need to alter the approach in order for this to work, we can’t just give it a list of device names. We have to have a list of objects that have a matching “DeviceName” property that will correspond to this parameter.

# Construting a list of objects with a devicename property

$devices = @(

@{

devicename = "My-PC-Name"

},

@{

devicename = "Your-PC-Name"

},

@{

devicename = "Other-PC-Name"

}

)

# Accessing the first device's devicename property

$devices[0].devicename

# Getting the type of the value

$devices[0].devicename.gettype()

We’ve now prepared an input for the pipeline that will be accepted. The Restore-LocalTime command’s -DeviceName parameter can now read pipeline input as long as it has a .DeviceName property.

$devices | Restore-LocalTime

This can now work (in theory), as we have moulded the pipeline input to correspond to the byPropertyName requirement.

One-At-A-Time

This is the final piece of the puzzle that ties everything together nicely.

When you pipe a list of items, PowerShell sends the items one-at-a-time

So let’s refer to one of the original commands:

Get-Service | Where-Object -property Status -eq "Running"

If you remember Get-Service by itself gives a huge list of results, and we use the pipeline to filter with Where-Object to only show the ones that are running.

The Pipe | sends each service from that first list, one-at-a-time. This is how Where-Object performs the filtering.

The output of Get-Service provides hundreds of services. The very first service, is then passed across the pipe as $PSItem or $_, then where-object reads the status property and checks if it matches the condition. This is why the Where-Object command can be written as:

Get-Service | Where-Object {$_.Status -eq "Running"}

The expression is essentially an if statement. And $_ represents the current selected item from the output of the left side of the pipe.

A breakdown of what’s happening:

$services = Get-Service

if($services[0].status -eq "Running"){

$services[0]

}

if($services[1].status -eq "Running"){

$services[1]

}

if($services[2].status -eq "Running"){

$services[2]

}

#...repeated until all services are processed

In essence, Where-Object is just checking if the current item’s property matches the condition, and outputting it if yes. If no, the check fails, and nothing happens (so the item is not outputted).

So remember that if you are ==piping== through several commands, each item is going through the pipeline one-at-a-time.

$list = @(item1, item2, item3)

$list | command-one | command-two

---

The above is then processed like so

---

$list -> | -> Command-One

Command-One item1 -> c1_output1

Command-One item2 -> c1_output2

Command-One item3 -> c1_output3

---

Command-One Outputs -> | -> Command-Two

Command-Two c1_output1 -> c2_output1

Command-Two c1_output2 -> c2_output2

Command-Two c1_output3 -> c2_output3

---

Final Output

c2_output1

c2_output2

c3_output3

One way to think about it visually (feel free to ignore my insane ramblings here):

Let’s say your input is a bucket of tiny wooden blocks.

You have several machines, the machines take one block at a time and carve out a little bit. By the time a block makes it through all of them, you have a beautiful chess piece. Think of each machine as a command.

Next to each machine is a bucket, that you use to store the blocks that have ran through the machine.

So if we were to write this process like a PowerShell pipeline:

Bucket of wooden blocks | Machine 1 | Machine 2 | Machine 3

We sit down next to Machine 1, and start feeding it the blocks from our bucket. As the block comes out the other side with a chunk removed, you place it into the output bucket for that Machine 1.

Eventually, your “input” bucket is empty, and all the blocks are now in the Machine 1 output bucket. So you take the output bucket, and sit down next to Machine 2. You, again, one-by-one feed the pieces through the machine. Machine 2 is picky and discards some of the blocks that are put in. You simply feed in each block, and if it comes out, you put it in Machine 2’s output bucket until all are processed.

Then, with the output bucket of Machine 2, you sit down at Machine 3 and process the blocks. However, this time round when they come out the other side you don’t put them in an output bucket. As you place one in and it comes out the other side, you place it on the display for all to see (haha get it, display…yep).

Through this process all the wooden blocks from the initial bucket have either been discarded, or carved into some ==horseys==.

This is exactly how the pipeline works. One thing that might be inaccurate is the buckets, in PowerShell your items always go in a set order, rather than a bucket that you can randomly pick from.

A key point here is that final Machine 3, those “done” pieces are being put out to display as they are complete. This is true in the PowerShell pipeline, as items are processed they don’t come out all simultaneously. If that final command of the pipeline was especially intensive for a computer you would see the final data come out one item at a time.

Pipeline input =/= explicit input

Although I may have provided some simplified examples before-hand that equate commands like this together:

Get-Process | Get-Member

Get-Member -InputObject (Get-Process)

Knowing the (one-at-a-time) principle, very quickly describes that these two are completely different.

Where the first gives the process objects one-by-one to the Get-Member command. The second actually feeds the full list of Get-Process to Get-Member instantly. By running both you’ll see the results are wildly different.

The first will send each process to Get-Member, and will collect properties for each individual process, then at the end, eliminate the duplicates. Notice that right at the top of the output, Get-Member is showing the properties and methods for TypeName: System.Diagnostics.Process.

The second method where we provide (Get-Process) as an explicit input object, look at the very top of the results: TypeName: System.Object[]. Due to no pipeline, we are giving the whole array at once, hence the Object[] (Object Array) TypeName. So we are not gathering the nitty-gritty properties and methods for the process objects inside the list. We are getting the properties and methods of the list itself. Hopefully that makes sense, because I’m not doing another visual exercise for this one.