Data

Data can come in many types (some examples):

- strings (text)

- numbers

- Booleans (true or false)

- collections of the above

“Luckily” in PowerShell when you start out you don’t need to think about types, a lot of the time PowerShell will be able to figure out which ones you are using (PowerShell infers type, this can also bite you if you are not careful). But what you do need to know is how we group them into collections.

.getType()

A great starting point for figuring out what type of data something is, is to just query it.

$number= 11

'{0} is type {1}' -f $number, $number.getType()

$text = "word"

'{0} is type {1}' -f $text, $text.getType()

$Bool = $true

'{0} is type {1}' -f $Bool, $Bool.getType()

You’ll see the actual data type of a variable based on the data within it. You’ll notice the number 11 is System.Int32, this is because it is a 32-bit integer.

$decimal = 11.5

'{0} is type {1}' -f $decimal, $decimal.getType()

You’ll notice that a decimal number is of type System.Double

There are lots and lots of types for specific uses, if ever in doubt, refer to the PowerShell documentation for Types.

But please remember, sometimes, even if it looks like a number, that doesn’t mean it is a number. Verify if ever unsure:

$NumberForSure = "12,233"

"Surely, this $NumberForSure is a number: Type - {0}" -f $NumberForSure.getType()

This happens way more often than you would think, and for a lot of data types too.

Collections

Arrays

So let’s get to the fun bit, what if we want a collection of numbers. Easy, let’s make an Array:

$array = 1,2,3,4,5

$array

Cool, so how do I get only the first number of the collection?

Indexing

We need to do something called indexing (done with [] after an array), like in a book, we need to know what “page” it’s on…so first page:

$array = 1,2,3,4,5

$array[1]

You might have known this was coming, like in many languages the count starts from 0 rather than 1.

$array = 1,2,3,4,5

$array[0]

So what if I want the 2nd and 4th items. So indexes 1, and 3. We do so with a , in the index brackets:

$array = 1,2,3,4,5

$array[1,3]

Okay, what if I want the last 3 numbers. If this was a long array we wouldn’t want loads of numbers separated by commas. So we can use .. to ask for a between x and y number in the index brackets:

$array = 1,2,3,4,5

$array[2..4]

But wait a second, what if the array is very long? We won’t intuitively know the last index… I present to you, negative lookup:

$array = 11, 123, 343, 123, 432, 234, 213, 123, 5434, 12, 343, 5123, 54, 1234, 542344, 34, 123, 454, 454, 548, 597, 987, 2, 547

$array[-3..-1]

Using positive numbers we go from 0, but we can look backwards with -1, and so on. So we’re asking for the third to last value up to the last.

Some magic for you:

$array = 11, 123, 343, 123, 432, 234, 213, 123, 5434, 12, 343, 5123, 54, 1234, 542344, 34, 123, 454, 454, 548, 597, 987, 2, 547

$array[2..-1]

That should be enough to get you started with Array indexing. What about editing the contents.

Array editing

Let’s say we want to change the third value of the following array to a different value. We need the new value, and the index of the old value (in this case, 3rd item = Index 2)

$favouriteHobbies = "Reading,", "Video Games,", "Tidying."

"My Favourite Hobbies are: $favouriteHobbies"

"Let me correct that previous statement."

$favouriteHobbies[2] = "Avoiding my responsibilities."

"My Favourite Hobbies are actually: $favouriteHobbies"

That’s useful, but what if instead we want to add a value to our array. Well we can use the trusty += operator. If you don’t know what this is here’s a catch-up:

$number = 3

$number = $number + 1

$number

# Is the same as

$number = 3

$number += 1

$number

So for Arrays:

$array = "one", "two", "three"

$array += "four"

$array

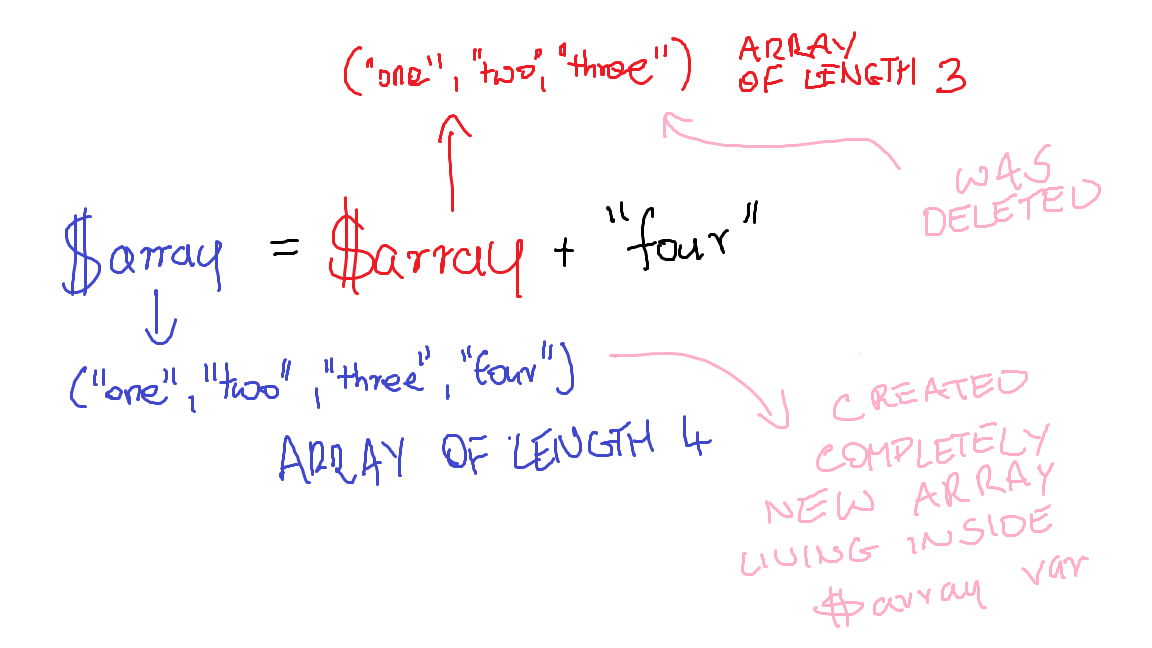

The issue here is, every time we are adding a value, we are creating a whole new array. This is because Arrays are of a fixed size, they cannot be increased. The $array you see at the first line of the last code block, is different to the $array you see on the last line. They have the same variable name, but that is a newly generated list.

Here’s a super professional explanation:

Let’s say we’re doing this over and over and over, well we’re reading the same array repeatedly and creating a new one constantly. This is computationally intensive. So not great if you just want to populate a list.

So let’s look at a slightly different type of Array, called an ArrayList.

ArrayList

Adding items to a regular array is one of its biggest downfalls. ArrayLists make this easier, they do not have a defined length like a regular Array. What does this mean? We can add stuff without creating a completely new Array.

# This is how we create an ArrayList, don't worry I never remember this, I just look up my own obsidian docs when I need to use this. I recommend making your own note that you can look up quickly

$ArrayListExample = [System.Collections.ArrayList]::new()

[void]$ArrayListExample.Add('AddedValue')

$ArrayListExample

We don’t need to write [void] before that addition, the only reason I do that is because this is what happens if I don’t:

$ArrayListExample = [System.Collections.ArrayList]::new()

$ArrayListExample.Add('AddedValue')

You’ll see that it now spits out the index that the ‘AddedValue’ is under. If you’re adding 10,000 of values to an ArrayList you’ll get 10,000 returned. So [void] at the start is a neat in-built method to supress this.

Turtles all the way down

Lists can contain Lists can contain Lists can con-

$Matrioszka = @(

@(

'Matrioszka1','Matrioszka2',

'Matrioszka3','Matrioszka4'

),

@(

'Matrioszka5','Matrioszka6',

'Matrioszka7','Matrioszka8'

)

)

If you’re a bit confused about how I define the arrays here, I am using the syntax @(item, item, item), up until now I was using the simple item, item, item declaration. However, in these more complicated structures it helps to enclose it in the @() structure to assist with indentation/readability.

HashTables

What if we want a collection of things that have their own properties. Like a list of games that have information about the games themselves. Well we can create something called a HashTable which has key = value pairs. Keys sort of act kind of like named indexes - but not really, so don’t commit to that thought, it just helps it make sense.

$game1 = @{

name = 'Path of Exile'

category = 'ARPG'

release = '2013'

}

$game1

Using a key to get its value:

$game1 = @{

name = 'Path of Exile'

category = 'ARPG'

release = '2013'

}

$game1.name

#or

$game1['name']

You’ll see it’s very similar to accessing values in an array.

Editing HashTable Contents

You can remove, specific keys likes so:

$game1 = @{

name = 'Path of Exile'

category = 'ARPG'

release = '2013'

}

$game1.remove('release')

$game1

Or add them:

$game1 = @{

name = 'Path of Exile'

category = 'ARPG'

release = '2013'

}

$game1.Add('developer', 'Grinding Gear Games')

$game1

That’s handy, but the output is not in the order that we created the HashTable in. Also, shouldn’t developer be on the end since we added it…that’s how arrays work isn’t it?

Ordered HashTables

By default HashTables just organise keys alphabetically, if we want a set order we can add the [ordered] keyword:

$game1 = [ordered]@{

name = 'Path of Exile'

category = 'ARPG'

release = '2013'

}

$game1.Add('developer', 'Grinding Gear Games')

$game1

Inline HashTables

What if you need to write the HashTable entry in one line, separate the key/value pairs with ;

$Wizard = @{name = 'Gandalf'; age = 24000}

$Wizard

If you’ve read Calculated Select-Object Properties you may notice this is how the calculated properties are declared.

Turtles all the way down again

$bigTurtle = @{

name = 'Bartholomew'

shellTenant = @{

name = 'Stephen'

shellTenant = @{

name = 'Patrick'

shellTenant = 'Earth'

}

}

}

$bigTurtle.name

$bigTurtle.shellTenant.name

$bigTurtle.shellTenant.shellTenant.name

HashTables in Arrays

A large chunk of data you will likely work with is lists of objects, most commonly PSCustomObject HashTables within ArrayLists.

Here’s how we can construct one:

$listOfObjects = [System.Collections.ArrayList]::new()

$Object1 = [PSCustomObject]@{name = 'Path of Exile';categories = 'Action RPG', 'Hack and Slash', 'RPG'}

$Object2 = [PSCustomObject]@{name = 'Elden Ring';categories = 'RPG', 'Action', 'Relaxing'}

$Object3 = [PSCustomObject]@{name = 'Insurgency: Sandstorm';categories = 'FPS', 'Realistic', 'Military'}

$Object4 = [PSCustomObject]@{name = 'Starcraft';categories = 'RTS', 'Strategy', 'Multiplayer', 'Competitive'}

[void]$listOfObjects.Add($Object1)

[void]$listOfObjects.Add($Object2)

[void]$listOfObjects.Add($Object3)

[void]$listOfObjects.Add($Object4)

$listOfObjects[1].categories[0]

The power of processing these types of Data Sets becomes obvious once we explain For-Each Looping